“Keeping Track of The Patients in The Congo”

One of the major administrative concerns of any Medical Clinic or Hospital is patient identification. Health cards, questionnaires, bracelets, monitors, records, computers etc. are all part of the process to ensure that the right patient receives the right medication or treatment at the right time.

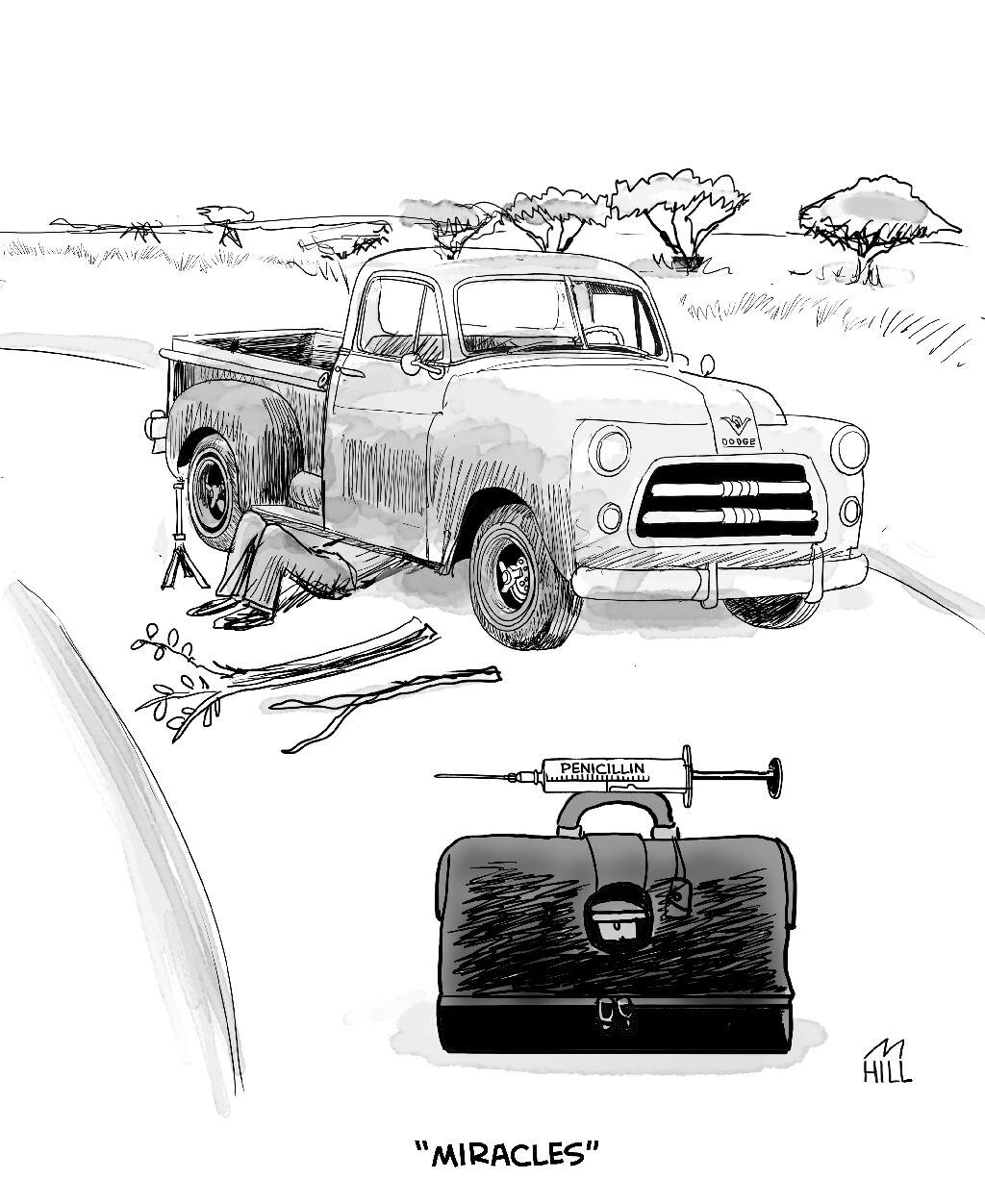

What would you do if you came to the Congo to set up a process to help meet a patient’s needs? You would find there were no computers, no health cards, monitors, and no questionnaires etc. to even begin any processing.

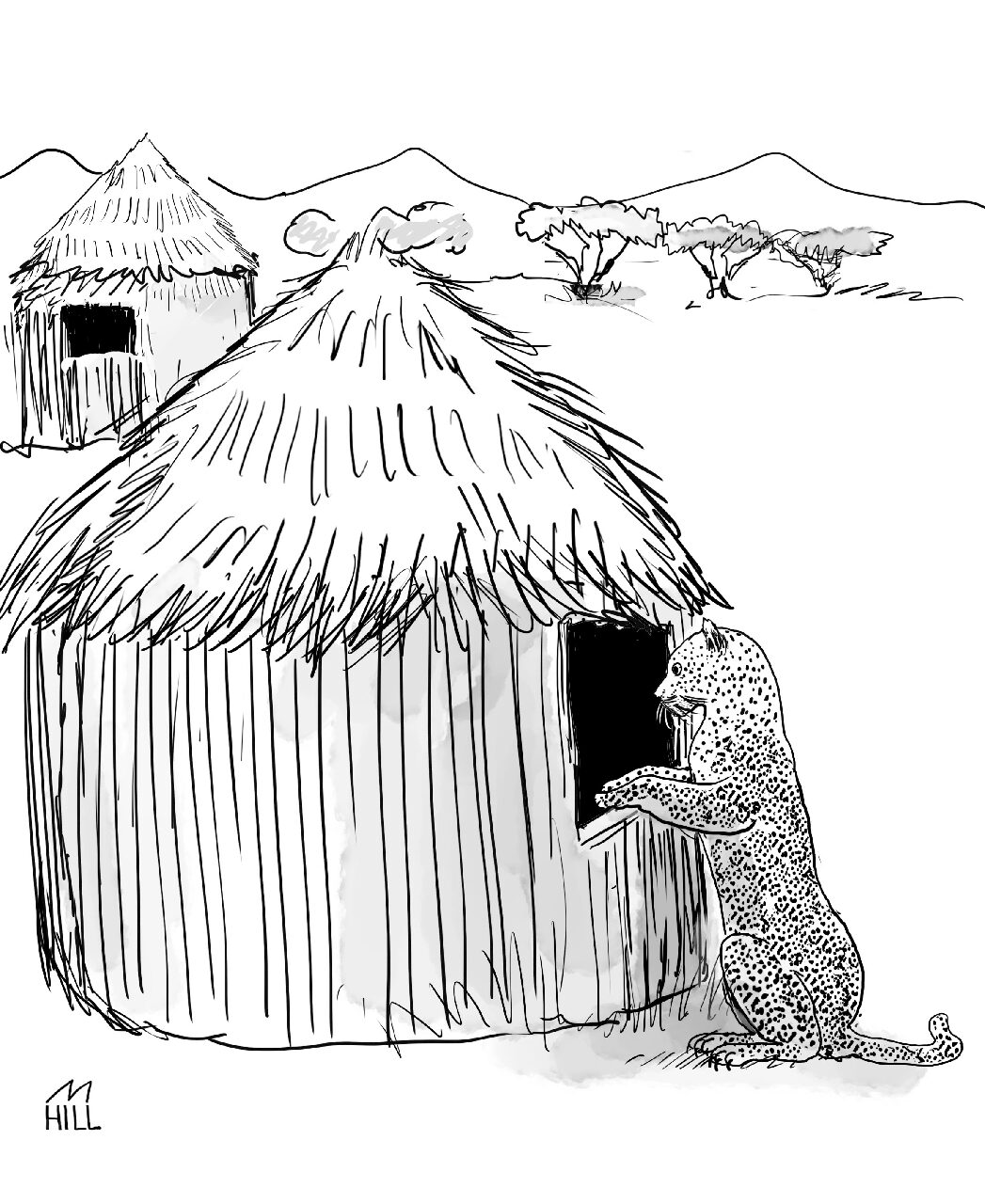

Furthermore, potential patients in the Congo do not have street numbers on their grass huts or structures that they live in. They often don’t even have streets. People can only vaguely indicate their residence by reference to a government building, church, school, or commercial establishment.

My real dilemma though was how would I understand patients when they came to me and how would they understand me.

The Democratic Republic of Congo is one of the most linguistically diverse countries in the world, with over 200 languages spoken in the country. While French is the official language and widely used in education and government, there are four national languages: Kikongo, Lingala, Swahili, and Tshiluba.

When I realized that God was leading me to the Congo instead of China which had been my first preference I began to prepare for work in Africa.

I had graduated from University of Toronto and started my first practice at Bella Bella in British Columbia This gave me some experience in a small hospital.

My next step was to go to Belgium to study Tropical Medicine and French at the Ecole de Medicine in Antwerp. My wife and I also stayed with a French couple that spoke no English.

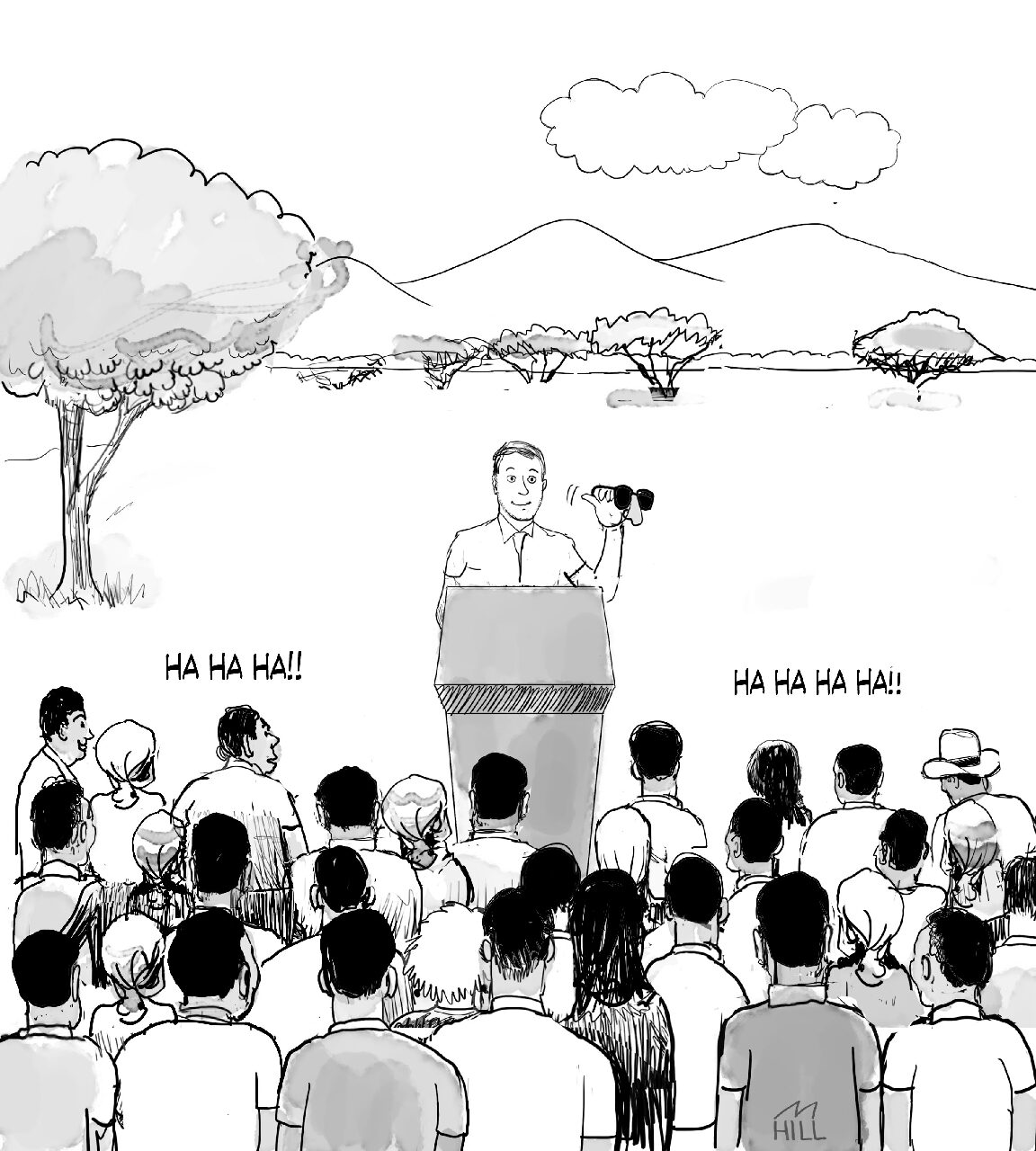

When first I arrived in the Congo, after a three week voyage, I worked with Dr.Becker who made certain that I had good initiation in the ways of providing care for Congolese people. I was able to replace him after six months and was on my own.During this time also I was learning to speak Swahilli.

Now that language was taken care of, I once again tackled the problem of patient identification.

Early on I developed a simple system that worked quite well. The ‘first’ patient was given the number one, the next patient got number two and others followed in sequence. Each patient’s number was transferred to a simple card system and the patient’s data of each visit was also recorded on their numbered card. This was simple enough but one still had to make sure that the patient remembered his number. I gave each patient a wooden chip 2-3 inches long, on which his or her number had been punched in by hand with a metal numbering system. A small hole was drilled at the top of each wooden tag so that it could be threaded by a string and worn around the neck or wrist. It was similar to a dog tag worn by soldiers around the world as a form of identification. All the patient had to do was to bring in his /her tag at each visit.

Many years later, some of the hurdles still exist. Patients still can be living in huts with no streets or numbers. Language can still be a barrier.

I wondered if patients are still given tags and required to show them for ID. I also wonder what numbers they are at now. I am sure that patient data would now be entered in by computer.